-

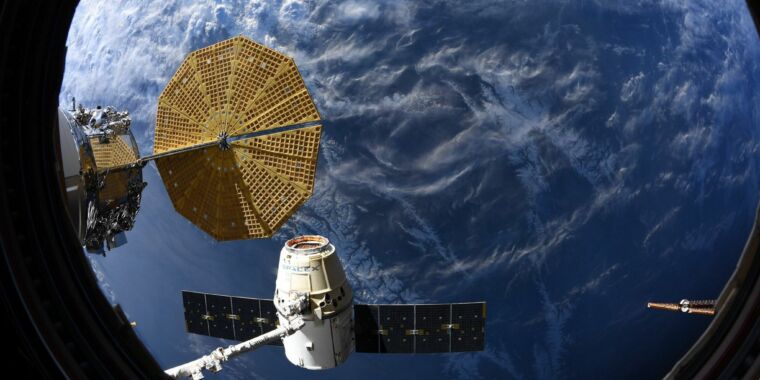

Cargo Dragon is shown on Tuesday, about to be released by the International Space Station's robotic arm.

-

This Dragon began its third flight on March 7, launching from Cape Canaveral.

-

It flew on a Falcon 9 rocket.SpaceX

-

Launch occurred shortly before midnight, local time.

-

Dragon is shown here, approaching the station.NASA

-

Getting closer.NASA

-

The station's robotic arm grabbed Dragon on March 9.NASA

-

We can't confirm it, but an astronaut may have said, "There be Dragons here" after docking.NASA

-

Just hanging out.NASA

-

From top to bottom, Andrew Morgan, Oleg Skripochka, and Jessica Meir are pictured inside the SpaceX Dragon resupply ship shortly after opening the hatch to the US space freighter.NASA

The date August 18, 2006, forever altered the trajectory of SpaceX.

On that day, NASA awarded SpaceX a contract to develop a service for delivering cargo to the International Space Station. This "Commercial Orbital Transportation Services" agreement would pay SpaceX $278 million to design and develop a spacecraft and rocket for this purpose—what became known as Cargo Dragon and the Falcon 9.

At the time, SpaceX was just 4 years old. The company had attempted a single launch, of its Falcon 1 rocket, from an atoll in the Pacific Ocean a few months earlier. This small rocket, capable of putting a few hundred kilograms into orbit, had flown for about half a minute before falling back to Earth and crashing into a reef just offshore. The rocket failed because, even before it cleared the launch pad, a fuel leak caused the engine to catch fire.

This was hardly a sterling record for a spaceflight company. So at the time, NASA was making a big bet on an SpaceX. Last summer I asked Gwynne Shotwell, then Vice President of Business Development for SpaceX, what this original NASA contract meant to the company in 2006.

"Oh, that was really important money," she said. "We were a little company. We were jackasses at that time. We'd just had a failure on the pad. We blew up a rocket in March of that year. Yeah, it was super critical. From my perspective, NASA was acknowledging that, even though we had a failure on Falcon 1, they felt like we had the right attitude and the right technology to extend this to a much larger rocket, the Falcon 9, and a capsule."

Getting Dragon to breathe fire

Over the next half-decade, SpaceX would design, develop, and test its Cargo Dragon spacecraft. As usual, the company looked to cut costs and upend the traditional aerospace model. For example, to store supplies for the ride into space, Dragon would need to have a mix of powered lockers (both to keep science experiments cold in refrigerators, as well as provide astronauts with a treat such as real ice cream) as well open bays that larger bags could be strapped into.

For the lockers, SpaceX sought out the vendor used by the space station program. The existing locker design required two latches to open and close each compartment, and the vendor wanted $1,500 per latch. This seemed way too expensive. Around that time, during a restroom break, a SpaceX engineer found inspiration as he contemplated the latch on a stall. Perhaps, he wondered, the company's in-house machinists might be able to make a similar latch. With $30 in parts, the company fabricated its own locking mechanisms that proved more reliable than the expensive, aerospace-rated latches.

Beginning in 2012, SpaceX flew its first cargo mission to the station. On Tuesday, Cargo Dragon completed its 20th and final flight to the station, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean. (For future supply missions, SpaceX will use a modified version of Crew Dragon, which has 20 percent greater volume and twice as much powered locker capacity).

Over the last eight years, various Dragon spacecraft have spent a total of 547 days attached to the space station, flown more than 450,000kg of cargo to the space station, and returned more than 35,000kg of science experiments and other cargo back to Earth.

For this service, SpaceX offered NASA a pretty good bargain. According to the space agency's own analysis, NASA's investment in SpaceX bought a service that cost as much as 10 times less than the traditional cost-plus contracting approach and two to three times less than the cost of continuing to fly cargo on the space shuttle.

The dominoes fall

In turn, SpaceX got a heck of a deal. From this initial award, it is not difficult to follow the dominoes falling in favor of the California rocket company. The NASA contract allowed SpaceX to rapidly expand its workforce from dozens to hundreds, investing in brilliant young minds to reach far-reaching goals.

NASA wanted tons of cargo sent into space on each mission, and this pushed SpaceX to a bigger rocket. So instead of the Falcon 5 (a booster with five Merlin engines) that Elon Musk and the company's engineers were planning as a follow-up to the Falcon 1, SpaceX jumped straight to the now-familiar Falcon 9 rocket. A rocket this size was large enough not just for NASA but to allow SpaceX to compete for both commercial satellite launches and large military payloads.

By flying the Falcon 9 rocket regularly for NASA, SpaceX was then able to glean valuable data about the flight profile of the first stage returning through the atmosphere. Through this process, SpaceX tested concepts such as supersonic retropropulsion, which enabled the use of Falcon 9 engines to control the rocket's return to Earth. This experimentation led directly to both land-based and sea-based landings of the Falcon 9 rocket.

In 2014, at least partly because SpaceX was successfully delivering cargo to the space station, the company was awarded a contract to deliver astronauts as well. The first Crew Dragon mission carrying Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken is now likely to occur in late May or June. Moreover, late last month, a modified version of Dragon, known as XL, was awarded a contract to deliver cargo to lunar orbit in the mid-2020s.

In less than 15 years, then, the jackasses have developed a spacecraft that has become something of a jack-of-all-trades.

Listing image by NASA

"last" - Google News

April 08, 2020 at 05:05AM

https://ift.tt/34kmkuS

The spacecraft that utterly transformed SpaceX has flown its last mission - Ars Technica

"last" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2rbmsh7

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The spacecraft that utterly transformed SpaceX has flown its last mission - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment