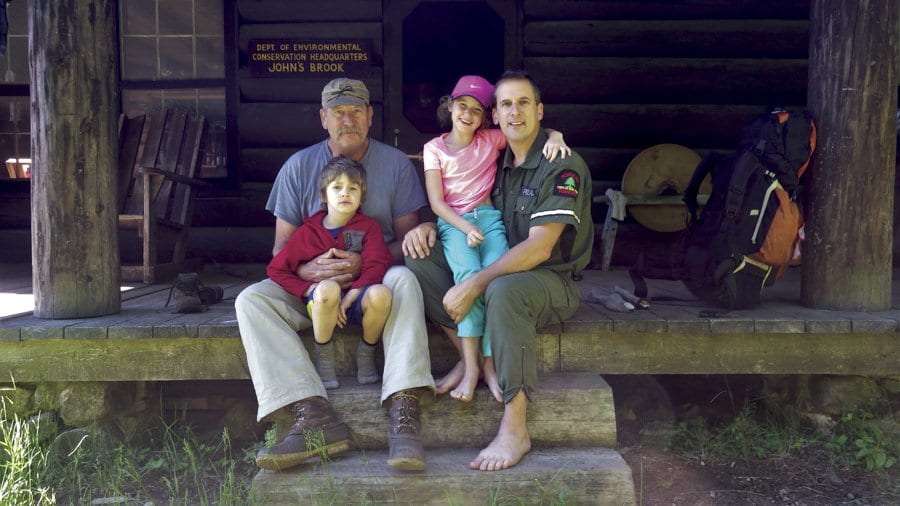

Scott van Laer ends run as forest ranger and ranger union representative

By Gwendolyn Craig

Scott van Laer’s sled was empty on the snowshoe trek from the Garden parking lot to the Johns Brook outpost in Keene. It wouldn’t stay empty for long.

It was March 7, and the hike was one of the last van Laer would make in uniform as a forest ranger with the state Department of Environmental Conservation. After 25 years of service, he was retiring. He headed toward the outpost to collect his things.

“I feel a little sad about it,” van Laer said, a small laugh bubbling up, then sinking. “A lot of good memories.”

In some ways it was like any other day, which is to say there is no typical day in the life of a ranger.

Van Laer was running on little sleep. Just hours before he had driven home from Allen Mountain after an emergency beacon was accidentally activated. You would never know it, though, as he greeted a group about a mile in on the trail the next morning.

The hikers weren’t wearing snowshoes and had an unleashed dog: two High Peaks rules broken. One man was wearing blue jeans, a dangerous choice because cotton does not dry easily. One man towing a sled stepped off the trail to let the ranger pass. Van Laer asked them to put their snowshoes on and gave the educational chat he had given thousands of times before.

“What happens is,” van Laer said while standing before the man sunk to his knees in the snow, “I don’t know if you can imagine this but, imagine you get off the trail to let somebody go by and you don’t have snowshoes on—and you sink down 2 feet.”

Chuckles.

Growing pains

Educating the public is central to a forest ranger’s job, but the duties have shifted since van Laer’s father wore the uniform.

Forest rangers in the 1970s roughly numbered one per 28,500 acres. Today, each accounts for more than 53,750 acres, as the state has purchased more land. Meanwhile, search-and-rescue missions have risen.

In the High Peaks, where van Laer has been stationed for about two decades, hiker numbers have jumped. On Cascade Mountain, one of the most popular High Peaks, van Laer has seen a doubling in the number of hikers between 2005 and 2015, to more than 33,000 people.

All of this, van Laer said, means there isn’t as much interaction with the public as he would like, and the long rescues and on-call demands are leading to ranger burnout.

Van Laer couldn’t seem to believe he was retiring at 48. “I thought they would bury me in my uniform,” he said.

He has led the call for the state to add more rangers, even foregoing a slated pay raise to convince DEC administration that rangers would rather have more staff. For six years, van Laer advocated as a union delegate with the New York State Police Benevolent Association.

That, he said, took the steam out of him.

“All the rescues and incidents were in some ways less stressful to me than the labor management battles that I had with the agency,” van Laer said about the DEC.

In response to van Laer’s advocacy, DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos has defended flat staffing, and has often pointed to how the DEC has conducted more forest ranger academies under his leadership. The commissioner has also lauded partnerships with State Police and other agencies to maximize existing resources.

This has been frustrating to hear for some state lawmakers, including the one who chairs the Assembly’s environmental conservation committee, Steve Englebright, D-Setauket. Each year, Englebright said, Seggos answers his staffing questions by saying, “We’re doing fine.”

“What does it mean in terms of the commitment of the administration to the protecting of the environment?”

Van Laer worries about leaving his colleagues, too. Three North Country rangers have retired in roughly six months. A spokesperson for the DEC said as of March 16 there were two vacant supervisory forest ranger positions and eight vacant field staff positions in the region.

DEC is also planning for another basic training academy. The department will then hire new forest rangers and environmental conservation officers “and phase them into service, and these positions transfer between DEC regions when openings become available.”

Special Offer

Subscribe to the Adirondack Explorer app for only $8!

Access a year’s worth of content from Adirondack Explorer magazine

on your mobile device, which includes our annual Outings Guide.

Use the code EXPLORE at checkout

The making of a ranger

Van Laer thinks the hiring system isn’t working.

“We get these mass waves of hirings,” he said, “but then we also get mass waves of retirement.”

When asked for a comment on retirements—van Laer’s and others’—a spokesperson said “DEC is grateful for the service of all DEC employees who retire from state service. While we cannot comment on pending retirements, with any employee retirement, DEC is always planning for the future to ensure our important work continues uninterrupted.”

Dick van Laer became a forest ranger with the DEC in 1977. He was stationed in Region 3 in the New Paltz area, but transferred up to Region 5 in Northville by 1988.

His young son, Scott, would meet him in the woods and spend the night. Sometimes, he would assist with a rescue or fighting a wildfire.

“I never put him in any situation where he would be in jeopardy, but he took to working in the woods and working with people quite readily,” the elder van Laer said.

His son said seeing his dad in the field “made me long for the job.”

Every generation of forest rangers experiences a shift in duties, Dick van Laer said, acknowledging the increased number of visitors and stresses his son has experienced on the job. In some ways, he said, technology has driven more search-and-rescue missions. More people rely on their phones to be a compass, map and flashlight. When the battery dies, they have no backup.

Heart and soul

Rangers are often on call 24/7 for searches, something that can be physically and emotionally draining, Dick van Laer said. He is proud of what his son has accomplished.

“Scott’s a young man, but he’s burned out,” he said. “He’s put his heart and soul into the job.”

Maybe ironically, search-and-rescues are what the younger van Laer said he will likely miss most.

“I think in time I’m going to miss the phone ringing,” he said.

He has responded to plenty of rings over the years. Some make him laugh, like the Memorial Day weekend when a couple set up a taco stand just below the summit of Mount Marcy, the highest peak in the state. He remembers letting them serve the last taco they were cooking up before shutting the operation down and ticketing them.

“I remember some of the people were angry because they were seeing the signs and said, ‘I was thinking all day about getting up here and getting my taco,’” van Laer said and laughed.

Other calls have made him shake his head. There were plenty of times when a worried person would call dispatch and ask if someone could get on the loudspeaker to the Adirondack Park and call out for their friend or loved one. They didn’t know the park covers some 6 million acres.

Then there were calls that made him proud of the teamwork with his colleagues. They had saved a life.

One that stands out was on Saddleback Mountain in February 2018, when nearly three dozen forest rangers and a dozen volunteers helped save a hiker. That one was memorable, too, because one ranger sustained an injury. Everyone got off the mountain alive.

Not everyone survives the High Peaks, though, and a few searches haunt van Laer. They include a lost hiker that rangers found too late, and plane crashes, including on Lake Champlain.

Grateful hikers

Other searches had happier endings. There was one in 2018, when two experienced hikers had a mishap on Mount Marshall. Joan Renaud slipped and fell into a tangle of tree roots, impaling her leg. The weather was rainy and windy, and van Laer had to go full-speed up the mountain to reach her in time to harness her for a helicopter airlift during a break in the weather.

Renaud’s friend, Brenda Tirrell, recalled the incident for Adirondack Explorer last year. She said van Laer appeared “much sooner than we imagined possible.”

“When we expressed our amazement that he made it so quickly, he acknowledged sheepishly that he ran the whole way (carrying his 65-pound pack),” Tirrell wrote.

Van Laer said he was indeed going as fast as he could. That’s another reason he is retiring, he said. He believes his fitness level is declining. “It was getting harder to do the job, and then still be prepared for incidents.”

But the job is not all searches and rescues.

Get the magazine

This article first appeared in the May/June 2021 issue of Adirondack Explorer.

Sign up to have the magazine hit your mailbox seven times a year.

Kayla White, summit steward with the Adirondack Mountain Club, has worked with van Laer since 2014. His friendly and personable demeanor were always helpful when it came to educating hikers, White said, and he was always a great supporter of the stewards.

One time, while camping near Mount Marcy at Slant Rock, White saw van Laer hike up with a shotgun slung over his shoulder, she recalled. He was hazing black bears.

“It was a bad year for bears,” White said. “They were very active and were trying to get people’s food.”

The gun was a conversation starter, White added, and van Laer would explain to campers the importance of storing food properly.

“He was just a really great educator,” White said. “I will definitely miss him and miss seeing him out in the woods.”

Next chapter

It’s not the ending he imagined. Still, van Laer is not done with the Adirondacks.

The 1993 graduate of Paul Smith’s College is returning to his alma mater to become the new director of the college’s Visitor Interpretive Center (VIC). The nearly 3,000-acre campus offers educational programming, multiuse trails, places to camp and a Nordic ski facility.

Jon C. Strauss, interim president at Paul Smith’s College, said van Laer’s ranger experience, combined with his administrative duties with the union, make him a good person for the role. Van Laer is also charged with developing a new strategic plan for the VIC.

Van Laer wants to turn the center into a laboratory for trying new things such as closing down trails during amphibian migrations and bird nesting seasons.

“I’d like to see us do some of the things we’d like to be done on the 3-million-acre forest preserve that feels impossible,” he said. “Hopefully, we can do some of that on the 3,000 acres of the Paul Smith’s VIC.”

It’s a natural next step, he added, and he will continue to help educate the public and protect this wild part of the state.

Dick van Laer is happy his son will continue in an environmental job. “I’m very proud of the fact that he followed in my footsteps,” he said.

“He was a tremendous ranger.”

Sign up for one or more of our email newsletters and we’ll send you a guide to five short hikes around the Adirondacks, compiled from our series of “short hikes” guidebooks.

"last" - Google News

May 09, 2021 at 06:06PM

https://ift.tt/3vU0xHi

Ranger Scott van Laer's last patrol - Adirondack Explorer

"last" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2rbmsh7

https://ift.tt/2Wq6qvt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Ranger Scott van Laer's last patrol - Adirondack Explorer"

Post a Comment