We celebrate the 50th anniversary of Earth Day on April 22 in the midst of a pandemic, with the world slowed and hobbled by Covid-19. Yet Earth Day reminds us the planet still turns, the global climate and biodiversity crises still cry for attention, and nature still reveals its shimmering resilience. Google is honoring the occasion with a Google Doodle dedicated specifically to bees.

This Earth Day, as humans have retreated indoors to slow down the spread of the virus, we’re finding out how ecosystems respond to our absence from public spaces. Meanwhile, our planet as a whole, and our understanding of it, keeps changing at a frenetic pace. Average temperatures are rising, natural systems are degrading, our vulnerability is increasing, and science is advancing.

Even as many of us remain locked inside, there is still a big wide world out there with much to explore and discover. As part of a Vox tradition started by former Vox writers Brad Plumer and Joseph Stromberg in 2014, here are the seven most fascinating, impactful, and troubling things we’ve learned about our planet since the last Earth Day:

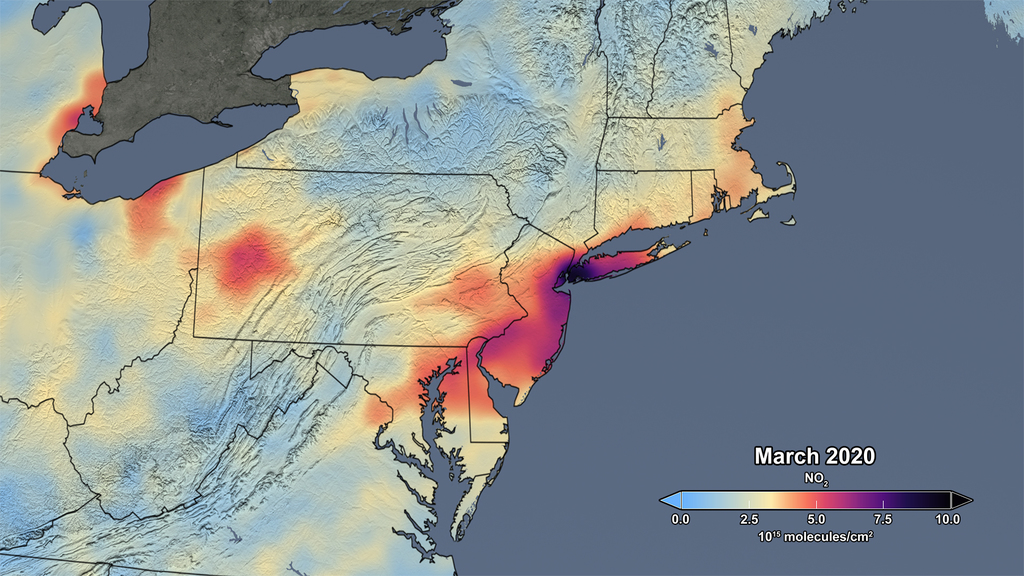

Sometimes you don’t notice something until it’s gone. Such is one stark visual lesson of the pandemic: air pollution is something way too many people around the world breathe in every day.

The shutdowns of business and travel during the Covid-19 pandemic have cleared the air in cities as pollution has fallen sharply. China, for instance, experienced a 40 percent decline in nitrogen dioxide, a pollutant produced from burning fossil fuels in cars and power plants, earlier this year compared to the same period last year.

Air pollution is a deadly threat, killing millions around the world every year. It’s also linked to more severe outcomes for Covid-19. Conversely, the economic slowdown stemming from Covid-19 showed that reducing pollution yields massive benefits for public health. One researcher estimated that the drop in air pollution in China saved 20 times as many lives as were lost to the virus.

And China isn’t the only place seeing clearer skies. In the United Kingdom, nitrogen dioxide pollution fell 60 percent after the country implemented a lockdown compared to the year prior. A nationwide lockdown in India revealed skylines and mountain vistas that had been obscured for decades.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown how quickly air quality can improve. But it doesn’t mean we should celebrate the pandemic for its impact on the environment. The clearer skies came at a devastating social and economic cost. The challenge for countries then is to reduce pollution without a massive toll.

Countries like China and the United States are weakening environmental regulations in the hope of helping industries better recover from the slowdown, so the pollution could come back with a vengeance. But it’s worth asking why we tolerated so much dirty air for the sake of the economy for so long and whether there’s a better way.

Though we still don’t know exactly when or where the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, spilled over from wildlife to humans, scientists who’ve analyzed its genome say it appears to have originated in wild bats.

We shouldn’t be surprised humans got infected with a dangerous pathogen that was circulating in wildlife; with more and more people encroaching further into wild areas, the threat of an event like this has been clear. Scientists who study emerging infectious diseases have been warning about this scenario for years. The 2003 SARS outbreak (which also passed from animals to humans) ought to have been a wake-up call. Yet the big lesson from SARS-CoV-2, which has infected over 2.5 million people and killed over 176,000 as of April 21, is that our efforts to stop these viruses before they start ripping through human populations have been woefully insufficient.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19916218/GettyImages_492780959.jpg)

“Every emerging disease that we battle with preexists in wildlife,” says Dennis Carroll, the former director of USAID’s emerging threats division who helped design Predict, a surveillance program for dangerous animal viruses that the Trump administration decided to shut down in October. If we’re not looking for the viruses out in the wild, he adds, and if we keep putting pressure on the ecosystems, then we’re likely to get smacked with another crisis like this one.

Pandemics, says Carroll, do not have to happen. “They are a consequence of the way we live. You can pick [viruses] up earlier if you’re really including in your surveillance those places where animals and people are having high-risk interaction, those hot spots.” Most of those hot spots are in East and Southeast Asia, but the international community can step up collaboration to monitor them. As this Covid-19 crisis has proven, contagious viruses can spread quickly around the world with the help of us increasingly connected, mobile, and urban humans. Since they can quickly become every country’s problem, it’s in every country’s interest to stop them.

Since last Earth Day, we’ve seen even more evidence that the great diversity of life on Earth is shrinking. Every year, we say goodbye to a number of species forever, and this past year was no different.

Creatures like the Chinese paddlefish and the Cryptic Treehunter bird were declared extinct in the past year. Others like the Sumatran Rhino are rapidly receding, now extinct in many of the places they once lived.

These extinctions were driven by habitat loss, overfishing, competition from invasive species, and climate change. But it’s a trend that’s been building for a long time, and over the past year, researchers revealed the astonishing pace at which these unique forms of life are disappearing.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19433735/1163345271.jpg.jpg)

We’re losing life at a larger scale than we realized. For instance, more than a quarter of all birds have vanished from the United States since 1970, a loss of nearly 3 billion animals. Over the past decade, 467 species were declared extinct.

And it’s not just the number of species lost that’s so alarming; the loss of biodiversity since humans started walking the Earth 200,000 years ago is vast. To replace just the mammal species that were lost in that time, researchers estimated last year it would take between 3 million and 7 million years of evolution to restore that kind of variety.

Biodiversity might be contracting, but our understanding of it is not. Most species of plants and animals have yet to be discovered. And each year, we learn about more.

Since last Earth Day, scientists have discovered that there are three species of electric eel — for the past 250 years, researchers had thought there was only one. (The eels have been hard to study, because, well, they are shockingly hard to handle. The Atlantic’s Ed Yong describes touching one as like being hit by a taser.)

A single scientific institution — the California Academy of Sciences — added 71 new plant and animal species discovered on five continents and three oceans to the record in the last year. Those included a purple iridescent fish named cirrhilabrus wakanda after the fictional kingdom of Wakanda (from the Marvel Black Panther comic and movie), 15 species of gecko, and six sea slugs.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19916248/Screen_Shot_2020_04_21_at_6.13.01_PM.png)

Meanwhile, scientists learned that 10 apple varieties that were thought to be extinct were still around in rural fields and ravines in Idaho and Washington state, Smithsonian reported. And recently, for the first time ever, evolutionary scientists have documented how flowers try to save themselves after being knocked down. After an insult, the individual flowers on the stalk will rotate back, as best they can, into a position ideal for pollination.

These findings are reminders that there are many more discoveries waiting to be found. Even discoveries of life long since gone: This past year also saw a new study digging into the core of the crater of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Earth today is pleasant compared to the cataclysm of tsunamis, wildfires, and molten earth that followed that catastrophe.

The ferocious bushfires across Australia in late 2019 and early 2020 illustrated what happens to an already volatile climate as average temperatures rise and offered a window into the future for the rest of the planet.

The blazes ignited in 2019, already Australia’s hottest and driest year on record, and went on to burn more than 27 million acres, destroy more than 3,000 homes, kill at least 29 people, and send smoke around the world. The fires also killed more than a billion animals in some of the most unique and fragile ecosystems on the planet.

Volatile weather is a signature of Australia’s climate. The continent sits in the middle of three major ocean circulation systems, so it’s often vacillating between extremes. In 2019, those circulation patterns aligned in such a way to drive moisture away and trap heat.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19916264/84754411.jpg.jpg)

But long-term changes are also underway. The fires emerged after years of drought, leaving vegetation primed to burn. And Australia’s climate has warmed by just over 1 degree Celsius since 1910, slightly faster than the global average. Rainfall patterns have shifted too, with more in the north and less in the southeast, where most Australians live.

So natural variability on top of climate change created the conditions for Australia’s devastating fires, with trends that were building for decades suddenly wreaking havoc over the course of weeks. Australia’s fire season is getting longer and more dangerous as well.

Though other countries may not regularly face Australia’s temperamental weather, they would do well to heed these risks as temperatures continue to rise. “Particularly in southern Australia, it sort of maps relatively similarly over other areas in the mid-latitudes, what we’d think of as the Mediterranean zone. So it’s the Mediterranean proper, like Spain and Italy and Greece, but [also] California, the tip of South Africa, [and] over in Chile and Argentina,” said Mark Howden, director of the Climate Change Institute at the Australian National University. “So all of those latitudes around the same as Australia, they’re getting drier, are getting hotter, having more problems in terms of water, in terms of agriculture.”

In the past year alone, the spaceflight company SpaceX has launched more than 360 small satellites into near-Earth orbit with the goal of using those spacecraft to build a worldwide internet access service. They’re just getting started. In all, the company has approval from the Federal Communications Commission to launch 12,000 satellites, and Musk is seeking approval to launch 30,000 more.

The problem is that these satellites are bright, and they are already interfering with astronomers’ observations. Many scientists fear we’re beginning to lose a vital window into the heavens and a sense of our connection to the greater cosmos.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19571463/D00908899_i_r5001p01_CC_cleaned_2_2.jpg)

The problem is bigger than SpaceX; there are no international protections to ban bright objects in orbit. Even if an American company like SpaceX manages to darken its satellites (which the company says they are working on), another company in another country doesn’t have to. (And while SpaceX works on darkening its satellites, it keeps sending up the bright ones in regularly scheduled launches.)

Astronomers fear this is just the beginning. Soon, Earth may be blanketed by tens of thousands of satellites — many of which may be visible without a telescope — and they’ll greatly outnumber the approximately 9,000 stars that are visible to an unaided human eye. These satellites will bring telecommunications to some of the remotest parts of the world, but possibly at a great cost to science and our view of space.

To help citizens cope with isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic, Iceland’s forestry service encouraged people to hug trees instead of other people.

But trees do more than keep us company; they are an important bulwark against climate change, cooling the air around them, capturing and storing carbon, supporting other species, and cycling moisture.

Protecting and restoring forests is then crucial for the planet. A research team last year found that helping forests recover and regenerate could soak up a large share of all the greenhouse gas emissions humanity has ever produced. Other researchers were skeptical of the scale of these calculations but otherwise agreed that nature-based solutions like protecting forests are critical to fighting climate change.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19428471/4O2A9096.jpg)

Yet the world also received a shocking glimpse in the past year of how vulnerable even the mightiest forests can be. The Amazon rainforest, the world’s largest tropical forest, suffered its highest rate of decline in more than a decade in 2019 driven by logging, mining, and agriculture.

There was also a huge increase in the number of fires in the Amazon. With so much rain, the Amazon rainforest does not experience wildfires, so researchers said the blazes were deliberately ignited to clear the forest, spurred by tacit approval from Brazil’s government. The fear now is that the forest is edging closer toward a self-destruct cycle known as a dieback.

The Amazon fires helped galvanize international attention toward protecting forests. And one thing that’s become clear since the last Earth Day is that people really like planting trees.

The United Nations’ Green Climate Fund raised almost $10 billion from donors last November to finance projects including forest restoration in developing countries. Philanthropists at the World Economic Forum announced their support for the Trillion Trees Initiative, aimed at planting scores of trees around the world. Even President Trump, who has been disdainful of acting to limit climate change, touted his support for the program during his State of the Union address this year.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

"last" - Google News

April 22, 2020 at 11:04AM

https://ift.tt/2RVvlG3

Earth Day 2020: 7 things we’ve learned since the last Earth Day - Vox.com

"last" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2rbmsh7

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Earth Day 2020: 7 things we’ve learned since the last Earth Day - Vox.com"

Post a Comment