Larry McMurtry's third novel, 1966's "The Last Picture Show," is a brutal book that sizes up the North Texas plains as a killing floor for human dreams and dignity that Thomas Lask, the longtime poetry editor of The New York Times, described as "a place in which a man can live all his life and end up feeling anonymous."

The principal setting is Thalia, Texas, a fictional place based on McMurtry's actual hometown of Archer City. But another Thalia, Texas exists — an unincorporated community where about 100 people live, about 60 miles (as the crow flies) northwest of McMurtry's Thalia/Archer City.

In the 1971 movie "The Last Picture Show," the name of the town is changed from Thalia to Anarene in part because director Peter Bogdanovich saw his movie as an homage to Howard Hawks' 1948 film "Red River," set in Abilene, Kan.

Anarene was evocative of Abilene, he thought, so he changed the name. There seems to be no record of McMurtry objecting, probably because, like Shakespeare said, any name is as good as any other once you get used to it. Bogdanovich was a director with aspirations and meant to seed his film with allusions to the films of directors he admired. Anarene was just as good a name for a dead-end town as Thalia — they could even play Archer City in football, which they do in the movie version.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mvgKGY5m71w]

I screened the movie the other day, kind of by accident. The day before my LifeQuest of Arkansas movie class, I discovered that something had gone hinky with my copy of Charles Burnett's "My Brother's Wedding" (I was planning to show the 82-minute director's cut that was released in 2007 instead of the 156-minute unfinished version that was briefly released in 1983) and needed to come up with a backup plan.

I had been thinking about Cloris Leachman, who died in January, and who won a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award for her role as Ruth Popper, the frustrated wife of the closeted Anarene High School football coach (the coach's secret is made more explicit in the novel, but there are hints of it in the film) who seeks solace with protagonist Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms), a withdrawn and occasionally kind-hearted high school football player.

I had a copy of "The Last Picture Show" on hand, and even though I didn't have time to watch it before class and make notes, I was familiar enough with the film to wing a lecture about it.

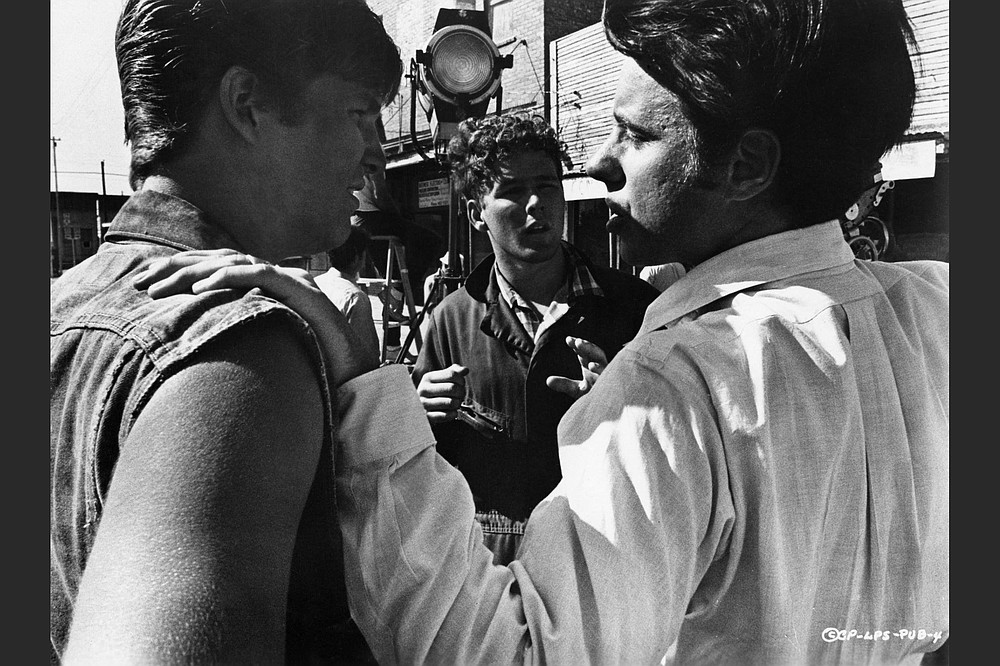

After all, I had heard the story about Dennis Quaid being cast as the "idiot kid" Billy only to be replaced when Bottoms brought his little brother Sam to the set (which was the actual Archer City) to get him away from their bickering parents, who were hurtling toward divorce.

Not knowing who he was, Bogdanovich saw 15-year-old Sam sitting in front of the pool hall and asked him if he'd ever done any acting and if he'd like to be in his movie. Sam, who'd been involved in community theater back home in Santa Barbara since he was 10 years old, shrugged and mumbled "dunno." Bogdanovich had to have him after that.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FQunyqgIksc]

I'd also heard the story that, after the big New York premiere of the film, Cybill Shepherd's mother had leaned over and patted her daughter on the arm, telling her, "You'll do better next time, dear."

When I first saw the film, probably as a freshman in high school, it was exhilarating, and I envied the characters Sonny and Duane Moore (Jeff Bridges), recent high school graduates loosed into an R-rated adult world.

Though some of my students remember the film being X-rated, with no one under 18 being allowed in under any circumstances, it was only banned in Phoenix and briefly in Rapides Parish, La. But it is racy enough that Orson Welles called it a "dirty movie," and one way to look at it is as a movie brat exploiting the classic visual grammar of old Hollywood to class up a smutty soap opera. There is literally nothing to do in Anarene/Thalia/Archer City other than play/watch high school football and chase sex, so everybody does that, even as they find it narcotizing and self-obliterating.

What I didn't understand at 14 was how sad and true this story was.

Anyway, "The Last Picture Show" — the film primarily, though the differences between it and the novel are minor; the novel covers more ground — begins in December 1951, the morning after the Anarene football team's season ends with a loss and wraps up about a year later, just after the team has ended another losing season.

It opens with a camera panning the deserted streets of what could be, but for the low banality of the architecture, a studio-lot Western town. Robert Surtees' camera catches — its black and white footage recalls both the deep-focus camera work of "Citizen Kane" cinematographer Gregg Toland and John Ford's "Stagecoach" — a gritty wind and a swirl of dead leaves, revealing a figure ineffectually sweeping the middle of an intersection with a broom, a nifty metaphor for how everyone in Anarene must feel.

This is Billy, who is soon rescued by Sonny, who parks his pickup he shares with his best friend Duane, gets out and turns Billy's baseball cap around backward as he leads him into the pool room owned by Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson).

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TdA9tMhGZi4]

Sonny and Billy look so much alike that there is no mistaking their actual brotherhood, which is something I once considered a minor flaw because in the book (and the movie) there's no indication that they are related. But now I think it's not only possible but likely they are half-brothers or perhaps cousins; they might even, on some blood-deep level, know this about each other.

Anarene is, like most dead-end places, an incestuous place where you can visit the local diner Sunday after church and see the generations devolving: Grandpa, tall and lean, crisp in his snap-button shirt and bolo tie; his son running a little jowly and civic-club prosperous with a Ban-Lon golf shirt over his easy bulk; grandson loose and sloppy with white gravy on his Longhorn jersey. Sonny and Billy are of the same tribe.

Duane is more than Sonny's best friend. In the book, they share a room in the boarding house (both their families having splintered) and that pickup, which Duane hoards on Friday and Saturday nights. Duane is crueler than Sonny and, as an All-Conference fullback, of slightly higher status. (Sonny, as his default girlfriend reminds him, only played on the line.)

McMurtry allegedly based the character on himself, which seems likely as the author made him the main character in four other books. Bogdanovich cast 21-year-old Bridges in the role because of his natural likability — you needed someone charming to play Duane, otherwise the audience would have hated him more than they did.

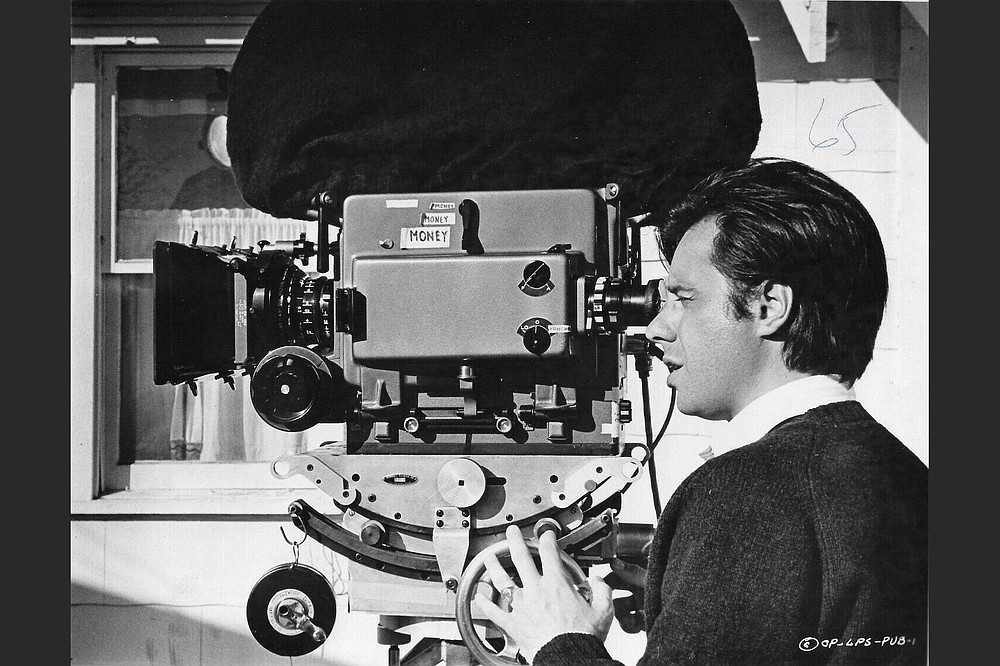

Bogdanovich was 32 years old when he made the movie; he had been a critic and a film historian working as a programmer for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Obsessed with film, he watched as many as 400 a year in the early '60s, before — following the example of the Cahiers du Cinéma critics Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and Éric Rohmer — he consciously decided to become a director. He headed for Los Angeles, skipping out on his final rent payment in Manhattan.

He insinuated himself into the industry, wrangling invitations to premieres from publicists in order to rub shoulders with directors and producers. Finally, Roger Corman remembered a piece he'd written and gave him his big break.

The result was "Targets" (1968), a plausible horror exploitation film based on the story of Texas Tower sniper Charles Whitman, a former Eagle Scout who killed 15 people in 1966, which Robert Evans bought for Paramount to release and brought Bogdanovich to the attention of major students, not least for what he was able to accomplish on a modest budget. ("Targets" was made for less than $150,000.)

Bogdanovich had another genre picture in mind for his next project; it was only after Columbia Pictures indicated they wanted "a more personal picture" from him that he considered McMurtry's novel. Actor Sal Mineo had given a copy of the book to Bogdanovich's wife, producer and screenwriter Polly Platt, lamenting that he was too old to star in a film of the book. She liked the material but didn't know if it was filmable. Bogdanovich thought he could bring something fresh to it.

He was a city boy who knew nothing about North Texas isolation and ennui.

Everybody knows Bogdanovich fell in love with Cybill Shepherd while they were making the movie. She was a 20-year-old model from Memphis who didn't know whether she wanted to make movies or go to college. Her character, Jacy Farrow, is by some lights the villain of the piece, an upper-middle-class ice queen who toys with the boys who pursue her, all the while looking to trade up and out of Anarene, to make it at least to Wichita Falls.

Because of Jacy, I thought you could call "The Last Picture Show" a misogynistic movie. But watching it again, I don't think that's right, because the women are the finest creatures in the movie and the book, and even Jacy is deserving of our compassion.

One of the greatest scenes occurs deep in the film, after Jacy allows herself to be seduced by smooth roughneck Abilene (Clu Gulager), her father's employee and the town cad. Abilene is taking her home, his car muffler rumbling in the night. Inside the Farrow house, Lois (Ellen Burstyn) — Jacy's mother and Abilene's lover — hears and recognizes the sound of his car. She waits, and we watch as anticipation glides over her face only to slide first into disappointment and then subdued, checked horror as her daughter enters, disheveled and upset. Burstyn remains silent as about eight different emotions break and wash over her face.

Another more famous but no less harrowing scene occurs earlier, when Sam the Lion delivers his famous speech at the water tank, where he's taken Billy and Sonny fishing, though the tank's unstocked except for turtles. Sam talks about how he used to water his horses at the tank more than 40 years before, and how he used to own the land around it.

"I reckon the reason why I always drag you out here is probably I'm just as sentimental as the next feller when it comes to old times," he says. "Old times. I brought a young lady swimmin' out here once, more than 20 years ago. Was after my wife had lost her mind and my boys was dead. Me and this young lady was pretty wild, I guess. In pretty deep. We used to come out here on horseback and go swimmin' without no bathing suits.

"One day, she wanted to swim the horses across this tank. Kind of a crazy thing to do, but we done it anyway ... [S]he was always lookin' for somethin' to do like that. Somethin' wild. I'll bet she's still got that silver dollar ... Being crazy about a woman like her is always the right thing to do."

That speech likely won Johnson his Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. The story is he didn't want the part, that there were too many words for the old character actor. His friend John Ford convinced him to do it, because he didn't want Johnson to be remembered for "playin' second fiddle" to John Wayne.

We later find out the woman he's talking about is Lois, who is now running around with Abilene. Armed with that knowledge, let's return to the movie's opening scenes, when Abilene — who, per the novel, pays Sam $250 a year for his own key to the pool room so he can practice anytime he wants — first appears.

He walks into the pool room to collect a bet from Sam, who naively bet on the Anarene football team. Sam hands him the case with his custom pool cue that Abilene begins to screw together. The two men don't make eye contact. Abilene's motion is unmistakably aggressive; Sam is stoic but seething. Sam loves Lois; for Abilene she's just something to do.

Bogdanovich wanted to shoot the film in black and white, but didn't think it was a possibility until Welles — who had befriended him while working on a documentary about Mike Nichols' "Catch 22" — told him it was the only way to go. "The Last Picture Show" was an actors' movie, Welles said, and he had never seen a great performance shot in color.

That might have been true for someone of Orson Welles' generation, but for a modern audience, the black and white cinematography works as a nudge toward classicism. We tend to respect it for its gray-scale integrity, to see it as something timeless. It's more of a trick for us than it might have been for them — it emphasizes the bleakness of Anarene, but a Technicolor version might be just as affecting. (Hal Wallis' "Red Sky at Morning," a coming-of-age movie set in New Mexico during World War II that was also released in 1971, is not as well-written or realized as "Last Picture Show," but its color cinematography is quite nice.)

What might strike the modern viewer as most remarkable about the film is its complete lack of nostalgia for the early '50s, which were just 20 years distant at the time (soon to be romanticized in movies like "American Graffiti" and "The Lords of Flatbush"). This is not the small-town America of Andy Griffith and Hooterville, but a hard, bitter, featureless place that nevertheless has a magnetic draw on its inhabitants.

Duane leaves for a while to work in the oil fields in Midland, and at the end of the book he's on his way to fight in Korea. The other characters are left in stasis, Sonny having inherited the pool room after the death of Sam the Lion. Lois continues in her loveless marriage. Maybe Jacy goes to college.

There is something pitiless and strange in this movie, which weds the directness of 0ld-school Western directors like Ford and Hawks (whose "Red River" shows up as the last picture shown in the movie house) with the freedom and permissive sweep of the late '60s cultural moment.

I saw this movie when I was 14, but I didn't really see it then. We never see the same movie twice.

Email: pmartin@adgnewsroom.com | blooddirtangels.com

"last" - Google News

March 21, 2021 at 02:43PM

https://ift.tt/3s66W0w

OPINION | CRITICAL MASS: 'The Last Picture Show' portrays ennui in Texas - Arkansas Online

"last" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2rbmsh7

https://ift.tt/2Wq6qvt

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "OPINION | CRITICAL MASS: 'The Last Picture Show' portrays ennui in Texas - Arkansas Online"

Post a Comment